This page contains automatically translated content.

The Long Way of the Good News

Image: Andreas Fischer.

Image: Andreas Fischer.Immenhausen, November 1958. A skylight opens. A beam of light penetrates the opening, cutting through the darkness. Grains of dust dance in it. For the first time in years, the roof truss of the rectory in Immenhausen near Kassel sees light again. Pastor Gerhard Oberthür enters the room, and with him a group of confirmation students. Stacks of old books appear in front of them. Darkness has shrouded them for decades, and with them the secrets they hold. It is November 16, 1958, Adenauer is chancellor, Schalke 04 is German champion, and Pastor Oberthür has just taken office in the small town of Immenhausen. One of his first official acts: Clean up the old rectory! When he and his confirmation students roll up their sleeves, no one suspects that they will come across a world sensation in the attic...

This is how it might have happened, the discovery of the Gutenberg Bible in Immenhausen. "Discovery? It was always there!" says Friedrich-Karl Baas (82), who identified the Bible without a doubt after almost 17 years of work, working together with Pastor Oberthür. You can tell Baas, a former school principal and church board member, has a passion for the Bible. "That was something special," Baas said. "Oberthür knew he had stumbled upon something significant. He didn't yet know that it was a Gutenberg Bible."

Mainz, around 1453. A revolution was underway in Johannes Gutenberg's printing workshop in the Humbrechthof, on what is now Schusterstrasse. After several experiments and smaller printing works, he succeeded - printing with movable type. Gutenberg's most important work: the printing of the Bible. No more laborious copying by hand, as clergymen did throughout the Middle Ages. The sacred text can now be printed en masse. The man from Mainz, born Johannes Gensfleisch, can be satisfied with his work. "The result of years of thought, untiring diligence, endless editions," the poet Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer had Gutenberg say in her drama of the same name. "i hold it here in my hand."

About 180 Bibles he printed. Apparently not a lot. The circulation of this "publik" edition alone is 5900. At the time, however, an advance like the Internet centuries later. For this, American journalists voted him "Man of the Millennium" in 1998. Dr. Brigitte Pfeil heads the Special Collections Department at Kassel University Library. She emphasizes the historical significance of the work: "It marks the beginning of the modern age in printing," says Pfeil. "Without Gutenberg's invention, the Reformation in the 16th century would not have worked the way it did." The face of Europe, perhaps the face of the world, would be different today.

Today, 49 Gutenberg Bibles remain in existence worldwide. One of them, number 48, made it to Immenhausen. But how did the Bible get to Immenhausen and then to Kassel? The search for clues begins in Mainz.

Mainz, June 2019: The Carmelite monastery in Mainz stands not far from the banks of the Rhine. The surroundings are not exactly reminiscent of early modern piety. Traffic is heavy on the Rheinstrasse. Across the street, a posh hotel flaunts. In the neighborhood there is a casino and a lingerie store. A monastery in the middle of the big city. Nevertheless, this is probably where the journey of the holy book began.

This is where the Immenhausen Bible found its first home. "With the help of the Marburg State Archives, we found out that the Bible probably came from the Carmelite monastery in Mainz," says Baas. Exactly when the Bible came to the Carmelite monastery is unknown. Here it probably served as a "chain book." So it lay chained in a scriptorium, a writing room, of the monastery and was studied by clergymen.

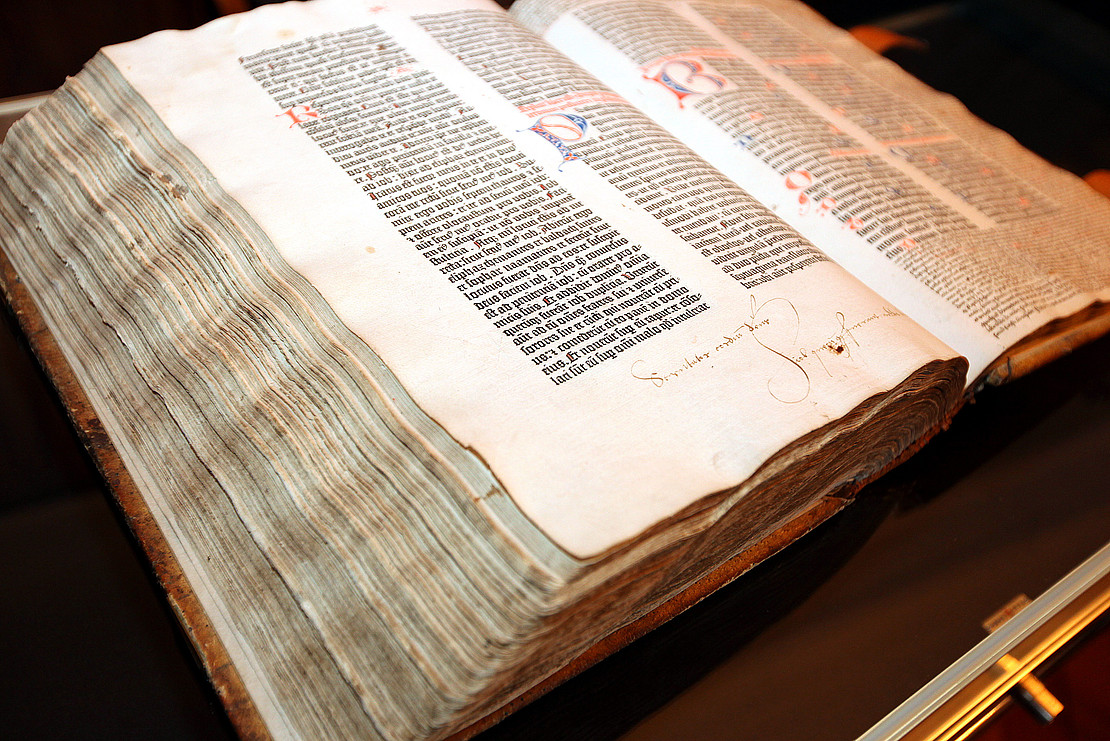

The Immenhausen Bible is modest, not a showpiece. "It is very plain," says Dr. Pfeil. Baas can confirm that. "The magnificent decoration of books was the responsibility of the buyers at that time." But the Bible, he says, did not serve a wealthy prince for adornment, but was needed for worship and study. Still, it has unusual features. "The initials, the capitalized first letters of each chapter, are all very ornately handwritten," Pfeil said. It covers only the first volume, which is the Old Testament.

The book didn't stay chained up for long. Around 1500, it came to Immenhausen. Why? We leave the Catholic bishop's town and jump into traditionally Protestant northern Hesse.

Immenhausen, June 2019. Immenhausen's St. George's Church is a gem. A small but beautiful and well-preserved early 15th-century Gothic church dedicated to St. George. Late medieval wall paintings adorn its interior. The Lutheran parish is the owner of the Gutenberg Bible. "It's nice to have such an important book," says Pastor Eckhard Becker. "It's historically very valuable." Baas adds, "...and it costs millions!"

From St. George, it's a short walk to what is now School Square. A quiet place between the Immenhausen volunteer fire department and the local Arbeiter-Samariter-Bund. Few may know that a convent stood here until 1631. The pious women maintained close contacts with Mainz. From there they also received Gutenberg's printed edition of the Bible.

"In addition to the Bible, Oberthür and his confirmands found a psalterium, a collection of psalms, and a missal, a liturgical missal," explains Pastor Becker. "These were typical utensils for the service. So the Bible was probably used for Mass in the monastery." It was probably a Mainz priest or monk who brought it from the Upper Rhine to northern Hesse. Sent by the bishopric of Mainz to care for the souls of the sisters. But who was the man? "We don't know the name of the priest at the moment," says Brigitte Pfeil. For the time being, a mystery of the Immenhausen Bible.

Wittenberg, the evening before All Saints' Day 1517. Hammer blows are coming from the Wittenberg Castle Church. A man stands in front of it. He hammers a thesis paper on the door. Martin Luther, a doctor of theology at the University of Wittenberg, is preaching against the sale of indulgences with his theses. In Rome, Pope Leo X, scion of the Florentine Medici banking family, claims that sinners can receive forgiveness at face value. Luther denied this. Conscience counts. And what the Holy Scripture says, not what the Pope thinks.

Whether the famous posting of the theses really took place is at least disputed among historians. But one thing is certain: The Reformation began. A Wittenberg theologian challenged the pope. A new church was founded and Europe was divided. This historic earthquake was also felt in Immenhausen. What is now northern Hesse joined the Reformation and became Protestant. The Marienhof monastery was secularized. And the Gutenberg Bible became the property of the Immenhausen parish. One of its users was Bartholomäus Riseberg, a student of Luther. It remained in Immenhausen for centuries.

Immenhausen, 1652. The Reformation did not make Europe more peaceful. On the contrary. Bloody confessional wars raged. The climax was the Thirty Years' War from 1618 to 1648, during which some regions in Germany lost half their population. The war also raged in northern Hesse.

In Immenhausen, the dust of war had just settled in 1652. The rectory was destroyed, but the valuable books of the parish survived the war well in the sacristy of St. George. Now they are to be moved to the rebuilt rectory. Parish priest Jeremias Kistener writes the handover protocol. He examines the books, including the Bible from Mainz, and shakes his head. "They are to be made into paper bags," he writes in the protocol. They should be made into paper bags, wrote historian Oskar Hütteroth in the early 1960s. However, this never happened and none of the successors took this advice seriously. Fortunately.

In 1708, the Bible was brought back to the sacristy together with other books, where it was stored in a Gothic cupboard. In the 19th century it was moved to the new rectory in Bahnhof Street. Here it fell into oblivion. Until one day in November 1958.

Kassel, August 22, 1975. Printing is different today than it was in Gutenberg's day. What the old master still did by hand, the HNA web offset press does fully automatically and much more efficiently. It fills an entire hall in Frankfurter Strasse, right next to the editorial office. The press is currently printing the new issue. On the cover, a picture of Friedrich-Karl Baas presenting the Gutenberg Bible. "Mystery of Immenhausen Bible solved after 16 years," writes the HNA. That the mysterious book is a Gutenberg Bible was unclear until then.

A lot of time passed until the riddle was solved. A first attempt by Pastor Oberthür to have the Bible identified was unsuccessful. In 1962, Baas took on the task. He suspected that it might have come from Gutenberg's workshop and studied it in detail. At the end of the sixties, he turned to the Murhard Library. The result: negative. The authenticity of the Bible could not be determined. Baas did not give up. At the beginning of the seventies, he wrote to specialist libraries in Darmstadt, Mainz and Munich. The result this time: a hit. Unanimous. The Immenhausen Bible is a Gutenberg Bible.

In 1975, it was ceremoniously presented to the public. It was then on display for several years in the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz. Finally, in 1978, it came to the Murhard Library, which is now part of the Kassel University Library. "The result of years of sense, untiring diligence." The real Gutenberg probably never said this sentence. But perhaps Friedrich-Karl Baas thought it when he presented the Bible to the public.

Kassel, July 2019. The Murhard Library is currently under renovation, the historic building surrounded by scaffolding. "At the end of the renovation work, the Bible will be displayed again and made accessible to the public," says Dr. Pfeil. Currently, the Immenhausen Gutenberg Bible lies locked away in an unknown location. It has come a long way from Mainz to Kassel. Unharmed by wars and revolutions. However, we do not yet know the name of the clergyman who brought it here. At least this secret is kept by the holy book.

Text: David Wüstehube

This text appeared - in a slightly different form - in publik 2019/3.