This page contains automatically translated content.

Of vegetarians and freedom fighters

Image: AP Photo

Image: AP PhotoFood is political - as demonstrated not least by the dispute over the ban on bratwurst at the Kassel "Earth Day". The discussion surrounding "Veggie Day" a few years ago also demonstrated the political explosive power inherent in the topic of nutrition, especially when it comes to the consumption of meat.

However, the issue of a meat-free diet is not a recent political issue; vegetarianism has been closely linked to political ideas since its beginnings as an organized movement. The goals that proponents and opponents pursued from the beginning of organized vegetarianism in the 1840s to the late 1950s are the subject of research by Prof. Dr. Julia Hauser at the Department of Global History / History of Globalization Processes at the University of Kassel.

The junior professor is particularly interested in the exchange between vegetarians in India and Europe. "Around the same time that the first vegetarian societies were founded in Europe, there was also an increased interest in the topic in India," Hauser says. "Meatless diets do have a centuries-old tradition among upper-caste Hindus, which was closely linked to the caste system. Since the late 19th century, however, there have been increased efforts in India to win over members of lower castes and the casteless to vegetarianism as well."

While in Europe during this time the main discussion was about how poorer sections of the population in particular could eat healthily in times of the industrial revolution, vegetarianism in India since the late 19th century was closely linked to the discussion about British colonial power.

"Only a strong body overcomes colonialism".

"Many British in India demonstratively consumed beef, citing the supposed physical weakness of Hindus, which was supposedly the result of their vegetarian diet, as an argument for their colonial subjugation," Hauser explains. In the late 19th century, Indian nationalists adopted this argument. "Some of them argued that meat-eating was inevitable to put an end to colonialism - only through meat could the body of the nation in the making become strong, and only a strong body could overcome colonialism," she writes in an essay.

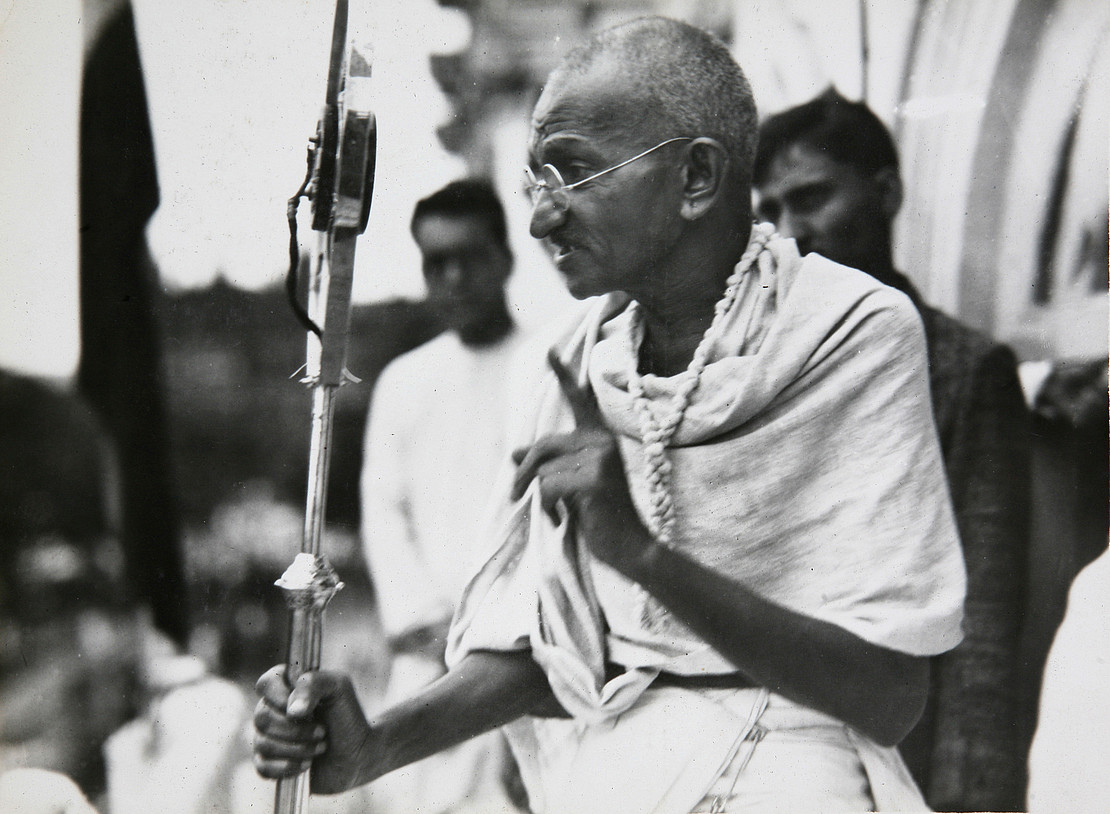

Other representatives of the Indian national movement, on the other hand, considered the vegetarian diet superior, both morally and in terms of health. The best-known representative of this group of anti-colonialists is Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, better known as Mahatma Gandhi, who became a member of the London Vegetarian Society while studying law in Britain and developed vegetarianism as central to his political program.

"What I find particularly interesting is that both sides made reference to each other - so in Indian publications on vegetarianism, you suddenly find patterns of argumentation from European vegetarians, for example about the physiological effects of vegetarianism," Hauser explains. "And there was also an exchange in the opposite direction - European vegetarians were inspired by Indian concepts of spirituality and purity," the junior professor explains.

The "frugal Oriental" - a German fallacy

In Germany, the focus tended to be on the Middle East. "The stereotype of the 'frugal Oriental,' who feeds mainly on bread, onions and salt, achieved some notoriety around 1900," explains the Kassel researcher. However, she adds, this perception was based on a misunderstanding: "It is likely that the explorers were simply not invited home by people during this period - because in the context of hospitality, meat enjoyed a high status in the region, while in the street scene, all that was actually seen was taking small snacks," she describes. The supposedly frugal "Orientals" were therefore by no means as frugal as the visitors from Germany thought.

Also with the alleged peaceableness of vegetarian living Hindus it was not so far. In Hindu nationalist circles, the killing of a cow had weighed just as heavily as the killing of a Brahmin. "Killing people who slaughtered cows was therefore more than legitimate," Hauser said. Gandhi, on the other hand, clearly set himself apart from this opinion in his politics, emphasizing the need to bring together India's diverse populations to protect cows while avoiding any form of violence. Still, since 2015 alone, at least 44 people in India have been killed by self-proclaimed cow protectors.

Text: Markus Zens, publik 4/2019