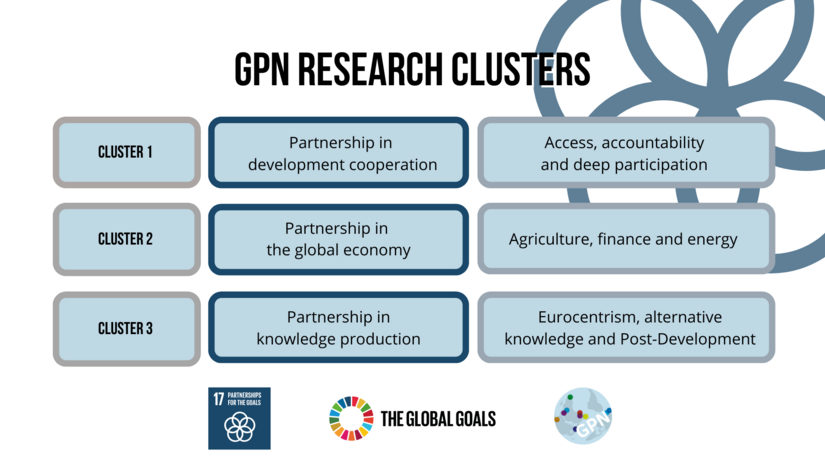

Research

Cluster 1: Partnership in development cooperation: access, accountability and full participation

Critical research on development cooperation has come to the conclusion that, despite its commitment to partnership (which was already expressed in the principles of the Paris Declaration of 2005 and in earlier concepts before SDG 17), it suffers from at least three problems: 1) Its benefits are unevenly distributed and rarely reach marginalized groups (especially women and indigenous peoples) (Kabeer 1994, Townsend 1995, Young 1995, Visvanathan et al. 2011, Radcliffe 2015, Mies/Shiva 2016). 2) It sometimes has contradictory, problematic or even catastrophic side effects (e.g. development-induced displacement) on the supposed beneficiaries or other project-affected people who can do little about it due to asymmetric power relations (Seabrook 1993, Ferguson 1994, Fox/Brown 1998, Clark et al. 2003, de Wet 2006, Easterly 2013). 3) Their participation mechanisms are limited by the structures of the development apparatus (Cooke/Kothari 2001, Hickey/Mohan 2004, Mosse 2005, Li 2007).

The GPN will therefore focus on the following points:

Access to development cooperation for marginalized groups and communities (women, indigenous peoples, ethnic minorities, LGBTIQ persons, persons with disabilities, racialized groups and people)

Accountability mechanisms and institutions in development cooperation, which has traditionally been dominated by trusteeships (Cowen/Shenton 1996)

On deep participation that includes not only equal partnerships and a high degree of ownership, but also an appreciation of local voices in defining problems and co-producing knowledge to solve them (Fam et al. 2017, Mauser et al. 2013, Siouti et al.2022).

The research cluster is therefore interwoven with research cluster 3 and aims to develop innovative, fair and sustainable models of partnership in development cooperation that meet the needs of a postcolonial world.

Cluster 2: Partnership in the global economy: agriculture, finance and energy

A serious pursuit of the SDGs requires partnerships in the global economy: the principle of policy coherence (officially confirmed since the Paris Declaration and central to SDG 17 Goals 13 and 14) states that successful poverty reduction must not be limited to development cooperation, but must go "beyond aid" (Browne 1999) and include coherent global governance in the various sectors of the global economy in order to prevent development policy measures from being thwarted by the foreign trade policy of donor states (Ashoff 2005, Messner 2005, Ziai 2007, see also BMZ 2017). also BMZ 2017). Global economic structures are therefore fundamental when it comes to a global partnership for sustainable development. The GPN will focus on three policy areas that are of particular importance for the SDGs and whose problem constellations and challenges underline the importance of strong partnerships: Agroecology, Finance and Energy. For these fields, there will be policy recommendations for policy coherence and successful partnerships in the global economy, in particular on the following aspects:

Agroecology: partnerships for change towards fair trade and organic agriculture (Raynolds 2000, Wienold 2012) and the abolition of forced labor (Gold/Trautrims/Trodd 2015). This area is particularly relevant for SDG 2 ("End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture"), SDG 15 ("Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems") and SDG 8 ("Decent work for all").

Finance: Debt relief initiatives and stakeholder networks (Browne 1999 Ch. 5, Caliari 2014, Vaggi/ Prizzon 2014), blended finance networks and investment partnerships (Pereira 2017, Mawdsley 2018, Attridge 2018, Clark et al. 2018) and microfinance initiatives (Aslanbeigui et al. 2010, Mader 2013, Duflo et al. 2013). This area is particularly relevant for SDG 8 ("Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth") and SDG 10 ("Reduce inequality within and among countries").

Renewable energy: Energy transition processes and local adaptation of energy technologies in post-colonial contexts (Parthan 2010, Müller 2017, Barthel 2023). This area is particularly relevant for SDG 7 ("Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all") and SDG 13 ("Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts").

In all three areas, GPN examines practical examples of partnerships and explores the reasons for success and failure, providing analysis and recommendations for policy coherence and partnerships in the global economy. This complements Cluster 1 by including policy areas beyond development cooperation that are critical to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

Cluster 3: Partnership in knowledge production: Eurocentrism, alternative knowledge and post-development

Knowledge sharing between partners is also part of SDG 17 (Goals 6 and 16), but whose knowledge should be shared? Post-development critique (Sachs 2010, Escobar 2012, Rahnema 1997, Rist 2014, Ziai 2018) has pointed to the Eurocentrism prevalent in development knowledge: Eurocentric ontologies assume a linear scale of social evolution with 'developed' (i.e. industrialized, secular, capitalist, democratic) European societies (including the European settler colonies in North America and Australia) at the top. This assumption, which e.g. implies that the knowledge of progressive social change that helps the global South to advance on this universal scale is to be found in the global North and that development experts possess this knowledge (Nandy 1988, Apffel-Marglin/Marglin 1990 and 1996, Mitchell 2002, Eriksson Baaz 2005, Ziai 2016), has been challenged by postcolonial theorists who emphasize mutual learning; alternative, local, non-Western (to be precise: non-hegemonic, because also found in the West) knowledge and pluriversal epistemologies (Connell 2007, Comaroff and Comaroff 2015, Santos 2007 and 2014, Bhambra 2014, Ndlovu 2014, Reiter 2018, Kothari et al. 2019) and alternative, participatory and decolonized ways of knowledge production and co-construction (Smith 2013, Bendix et al. 2020, Siouti et al. 2022, Narayanaswamy et al. 2023).

The GPN explores these alternative fields, structures and epistemologies of knowledge, their emergence, dissemination and translation, and the opportunities they offer for progressive bottom-up social change. By providing forums and fostering intercultural dialogue that includes marginalized populations, it will contribute to mutual learning and promote partnerships in knowledge production. In this way, Cluster 3 can also stimulate and enhance partnerships in development cooperation and global economic structures.

Overarching themes: Sustainability, coloniality, intersectionality

In the first phase, three overarching themes emerged in the research clusters: Sustainability, Coloniality and Intersectionality.

Sustainability became an overarching theme in response to the climate crisis and the need to find alternatives to the resource-intensive imperial modes of production and consumption of modern industrial societies (Brand/Wissen 2013). Without a strong sense of sustainability, global partnerships would reproduce growth models that exacerbate the problems of this mode of production and consumption. The topic is also closely related to the new Kassel Institute for Sustainability at the University of Kassel, which is associated with a number of new chairs and BA and MA programs such as Agriculture, Ecology and Society (AGES) or Critical Sustainability and Postcolonial Studies (CSPS).

Coloniality refers to the significant role that five centuries of colonialism have played in shaping relations between the global North and the global South, leading to asymmetries that still exist today (Quijano 2000). Without a reflection on coloniality, global partnerships would forget the historical debts incurred during these centuries, including the climate debt of the early industrialized countries. This theme intersects with the foci of the Chair of Development and Postcolonial Studies, the Chair of Modern History, the Chair of Sociology of Diversity and the aforementioned MA CSPS.

Intersectionality makes it clear that there is not just one type of power relation that acts as a universal key to explaining social and economic inequality at the global, national or local level (including colonial relations), but that the intertwined oppression of (at least) capitalism, racism, heteronormativity and patriarchy must be taken into account. Without intersectionality, global partnerships would bypass these power relations and possibly produce solutions that reproduce them. This topic is reflected in the new research center "Gender Studies in Transition" at the University of Kassel.

Apffel-Marglin, Frédérique/Marglin, Stephen (eds) (1990): Dominating Knowledge. Development, Culture, and Resistance. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Apffel-Marglin, Frédérique/Marglin, Stephen (eds) (1996): Decolonizing Knowledge. From Development to Dialogue. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Aslanbeigui, Nahid/Oakes, Guy/Uddin, Nancy (2010): 'Assessing Microcredit in Bangladesh: A Critique of the Concept of Empowerment', Review of Political Economy, 22: 2, 181-204.

Attridge, Samantha (2018): Can blended finance work for the poorest countries? ODI Insights https:// www.odi.org/blogs/10650-can-blended-finance-work-poorest-countries (Aug 1, 2019)

Ashoff, Guido (2005): Enhancing policy coherence for development : justification, recognition and approaches to achievement. Bonn: DIE.

Barthel, Bettina (2019): Renewable and decentralized energies from a postcolonial perspective. Ethnographic analyses of German-Tanzanian partnerships. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Bendix, Daniel/Müller, Franziska/Ziai, Aram (eds) (2020): Beyond the Master's Tools? Decolonizing Knowledge Orders, Resarch and Teaching. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bhambra, Gurminder (2014): Knowledge production in global context: Power and coloniality. Current Sociology 62 (4), 451-456.

BMZ (2017): Africa and Europe - New partnership for development, peace and the future.

Key points for a Marshall Plan with Africa. Berlin: BMZ.

Browne, Stephen (1999): Beyond Aid. From Patronage to Partnership. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Caliari, Aldo (2014) Analysis of Millennium Development Goal 8: A Global Partnership for Development, Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 15:2-3, 275-287.

Clark, Dana/Fox, Jonathan/Treakle, Kay (eds) (2003): Demanding Accountability. Civil-Society Claims and the World Bank Inspection Panel. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Clark, Robyn/Reed, James/Sunderland, Terry (2018): Bridging funding gaps for climate and sustainable development: Pitfalls, progress and potential of private finance, in: Land Use Policy, Volume 71, 335-346

Comaroff, J., & Comaroff, J. L. (2015). Theory from the South: Or, how Euro-America is evolving toward Africa. Routledge.

Connell, Raewyn (2007): Southern Theory. The global dynamics of knowledge in social science.Cambridge: Polity Press.

Cooke, Bill/Kothari, Uma (2001): Participation: The New Tyranny? London: Zed Books.

Cowen, M.P./Shenton, R.W. (1996): Doctrines Of Development. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

De Wet, Chris (ed.) (2006): Development-Induced Displacement. Problems, Policies, and People. New York: Berghahn.

Duflo, Esther/Banerjee, Abhijit/Glennerster, Rachel/Kinnan, Cynthia G. (2013): The miracle of microfinance? National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 18950.

Easterly, William (2013): The Tyranny of Experts. Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor. New York: Basic Books.

Eriksson Baaz, Maria (2005): The Paternalism of Partnership. A Postcolonial Reading of Identity in Development Aid. London: Zed books.

Escobar, Arturo (2012): Encountering Development. The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fam, Dena/Palmer, Jane/Riedy, Chris/Mitchell, Cynthia (eds) (2017): Transdisciplinary Resarch and Practice for Sustainability Outcomes. London: Routledge.

Ferguson, James (1994): The Anti-Politics Machine. 'Development', Depoliticization and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

Fox, Jonathan/Brown, L. David (eds) (1998): The Struggle for Accountability. The World Bank, NGOs, and Grassroots Movements. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gold, S., Trautrims, A., Trodd, Z. (2015) Modern slavery challenges to supply chain management. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 20 (5), 485-494.

Hirsch Hadorn, Gertrude/Hoffmann-Riem, Holger/Biber-Klemm, Susette/Grossenbacher-Mansuy, Walter/Joye, Dominique/Pohl, Christian/Wiesmann, Urs/Zemp, Elisabeth (eds) (2008): Handbook of Transdisciplinary Research. Springer.

Hickey, Samuel/Mohan, Giles (eds) (2004): Participation: from tyranny to transformation? Exploring new approaches to participation in development. London: Zed Books.

Kabeer, Naila (1994): Reversed Realities. Gender Hierarchies in Development Thought. London: Verso.

Kothari, Ashish/Salleh, Ariel/Escobar, Arturo/Demaria, Federico/Acosta, Alberto (eds) (2019): Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary. New Delhi: Tulika Books.

Li, Tania Murray (2007): The Will to Improve. Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

Mader, Philip (2013) Explaining and Quantifying the Extractive Success of Financial Systems: Microfinance and the Financialization of Poverty, Economic Research, 26 (s1), 13-28.

Mauser, Wolfram/Klepper, Gernot/Rice, Martin/Schmalzbauer, Bettina Susanne/Hackmann, Heide/Leemans, Rik/Moore, Howard (2013): Transdisciplinary global change research: the co-creation of knowledge for sustainability, in: Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, Vol 5/3-4, pp. 420-431.

Mawdsley, Emma (2018): 'From billions to trillions': Financing the SDGs in a world 'beyond aid', in: Dialogues in Human Geography 8 (2), 191-195.

Melber, H. (2018). Knowledge Production and Decolonization-Not only African challenges. Strategic Review for Southern Africa, 40(1), 4-15.

Messner, Dirk/Maxwell, Simon/Nuscheler, Franz/Siegle, Joseph (2005): Governance Reform of the Bretton Woods Institutions and the UN Development System. Dialogue on Globalization, Occasional Papers No. 18. Washington: FES.

Mignolo, Walter (2007): Delinking: The rhetoric of modernity, the logic of coloniality and the grammar of decoloniality. Cultural Studies 21 (2-3), 449-514.

Mitchell, Timothy (2002): Rule of Experts. Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity. Berkeley, University of California Press.

Mkandawire, T. (2011). Running while others walk: Knowledge and the challenge of Africa's development. Africa Development, 36(2), 1-36.

Mosse, David (2005): Cultivating Development. An Ethnography of Aid Policy and Practice. London: Pluto Press.

Müller, Franziska (2017): IRENA as glocal actor: pathways towards energy governmentality. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research. 30 (3), 306-322.

Nandy, Ashish (ed) (1988): Sciecne, Hegemony and Violence. A Reqiuem for Modernity. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Ndlovu, Morgan (2014): Why indigenous knowledge in the 21st century? A decolonial turn. Yesterday and Today 11, 84-98.

Ndhlovu, F (2017), 'Southern development discourse for Southern Africa: linguistic and cultural imperatives', Journal of Multicultural Discourses. (Available at: DOI: 10.1080/17447143.2016.1277733.)

Parthan, Binu/Osterkorn, Marianne/Kennedy, Matthew/Hoskyns, St. John/Bazilian, Morgan/Monga, Pradeep (2010): Lessons for low-carbon energy transition: Experience from the Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership (REEEP). Energy for Sustainable Development. (Available at: DOI: 10.1016/j.esd.2010.04.003)

Pereira, Javier (2017): Blended Finance: What it is, how it works and how it is used, Oxfam. https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/handle/10546/620186 (Aug 1, 2019)

Radcliffe, Sarah (2015): Dilemmas of Difference. Indigenous Women and the Limits of Postcolonial Development Policy. Durham: Duke University Press.

Rahnema, Majid with Bawtree, Victoria (eds.) (1997): The Post-Development Reader. London: Zed Books.

Raynolds, Laura (2000): Re-embedding global agriculture: the international organic and fair trade movements, Agriculture and Human Values 17: 297-309.

Reiter, Bernd (ed.) (2018): Constructing the Pluriverse. The Geopolitics of Knowledge. Durham: Duke University Press.

Rist, Gilbert (2014): The History of Development. From Western Origins to Global Faith. 4th ed. London: Zed Books.

Sachs, Wolfgang (ed) (2010): The Development Dictionary. A Guide to Knowledge as Power. 2nd ed. London: Zed Books.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa (ed.) (2007): Another Knowledge is Possible. Beyond Northern Epistemologies. London: Verso.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa (2014): Epistemologies of the South. Justice against Epistemicide. Boulder: Paradigm.

Seabrook, Jeremy (1993): Victims of Development. Resistance and Alternatives. London: Verso.

Smith, L. T. (2013) Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books Ltd.

Townsend, Janet Gabriel (1995): Women's Voices from the Rainforest. London: Routledge.

Vaggi, Gianni/Prizzon, Annalisa (2014): On the sustainability of external debt: is debt relief enough? Cambridge Journal of Economics 38: 1155-1169.

Visvanathan, Nalini/Duggan, Lynn/Wiegersma, Nan/Nisonoff, Laurie (eds.) (2011): The Women, Gender and Development Reader. 2nd edition. London: Zed Books.

Wienold, Hanns (2012): Fair trade: Moral economy or exchange of equivalents? Periphery No. 128, 500-508.

Young, Elspeth (1995): Third World in the First. Development and Indigenous Peoples. London: Routledge.

Ziai, Aram (2007): Global structural policy? The North-South policy of the FRG and the dispositif of development. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot.

Ziai, Aram (2016): Development Discourse and Global History. London: Routledge.