This page contains automatically translated content.

The social-ecological conscience of consumers

The problem of unsustainable development on our planet is one of the greatest challenges humanity has faced in its history.

The economic systems that ensure the "Western standard of living" in particular are accelerating climate change, the destruction of natural habitats and the irreversible consumption of non-renewable raw materials through often unsustainable manufacturing and logistics processes. As legal requirements for companies often fall far short of what is actually needed to ensure a good life on earth for future generations, numerous governments and ecological associations are pursuing the goal of giving consumers more responsibility (empowerment) and thus encouraging companies to operate more sustainably.

To this end, consumers are increasingly being provided with information on the socio-ecological value of products and services. This will enable them to better align their purchasing decisions with socio-ecological criteria and promote sustainable development. The various labels that highlight the social or ecological added value of certain products are already established and well-known measures. In addition, the EU Commission is currently discussing an action plan, for example, which aims to provide consumers with systematic and real-time access to information on the suitability of products for the circular economy.

However, these strategies only seem to be working to a limited extent. A look at the sales figures for products labeled as ecologically valuable shows that they still only make up a very small proportion of total consumption among consumers. Traditionally and often non-sustainably produced products still dominate. Even though "organic" is on the rise, it is still a niche market. What is particularly puzzling is that opinion polls show a completely different picture among consumers. Overwhelming majorities regularly state the central importance of socio-ecological value when selecting products. Their own values and actual purchasing behavior therefore do not match. Conscience dictates that consumers take socio-ecological criteria into account, but when it comes down to it, this view hardly seems to influence purchasing decisions. I investigated this contradiction in my dissertation and asked myself two central questions: Firstly, what does it even depend on that consumers still feel their conscience when they actually make purchasing decisions? On the other hand, do consumers simply switch off their conscience in certain situations in order to avoid the sometimes restrictive consideration of sustainability when choosing products?

Two large-scale experiments have revealed very interesting findings in this regard.

Initially, factors were identified from social and environmental psychology that could be relevant for conscience activation. In the experiments, the study participants were then confronted with products that contained obvious shortcomings in terms of sustainability. The test subjects were asked about the individual factors and the degree of "bad conscience" if they purchased the products. Statistical methods were then used to determine which factors were particularly relevant for the activation of conscience.

It depends on the emotions!

Respondents who were also emotionally affected by the socio-ecological problems of the product showed a much stronger conscience reaction than respondents who only "knew" in their heads that there was a problem. This circumstance provides, among other things, an explanation for the fact that the rather rational approach of purely providing information does not really have a profound effect on the conscience of consumers when they actually make purchasing decisions. Responsible actors should therefore consider how to communicate sustainability issues in such a way that they touch not only our minds but also our hearts.

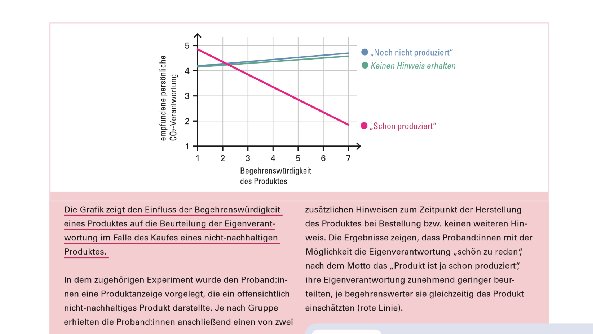

"Fine-talking"

Consumers tend to gloss over sustainability deficiencies or the purchase of a non-sustainable product! Test subjects who rated the products presented as fundamentally desirable apart from the sustainability shortcomings tended to make greater use of experimentally controlled opportunities to "whitewash" the sustainability shortcomings of the products than test subjects for whom the products were fundamentally less attractive. Desire thus dominates conscience. What is particularly interesting is that a kind of desire-driven blinkered effect was identified as the underlying mechanism. Test subjects simply ignored arguments that spoke against the "whitewashing" of the products' sustainability deficiencies if they also appeared desirable. This made the purchase of a desirable but non-sustainable product seem morally acceptable to the mind.

The results of the study help to better understand the sluggish development of sustainable consumption and show ways to further promote it. Emotions in particular play a central role in the consideration or disregard of socio-ecological aspects during the purchasing decision. Promotional approaches for sustainable consumption can benefit from these findings. At the same time, however, the limits of such approaches also become clear, as the decision of conscience is countered by the desirability of a product and limits the effectiveness of an emotional appeal. It is therefore conceivable that consumers who care about sustainability would even welcome stronger guidelines in these areas in order to avoid the constant and unpleasant conflicts of conscience.