This page contains automatically translated content.

Appetite-less, rare and 100 million years old: biologist finds new mosquito species in amber

Image: Patrick Müller.

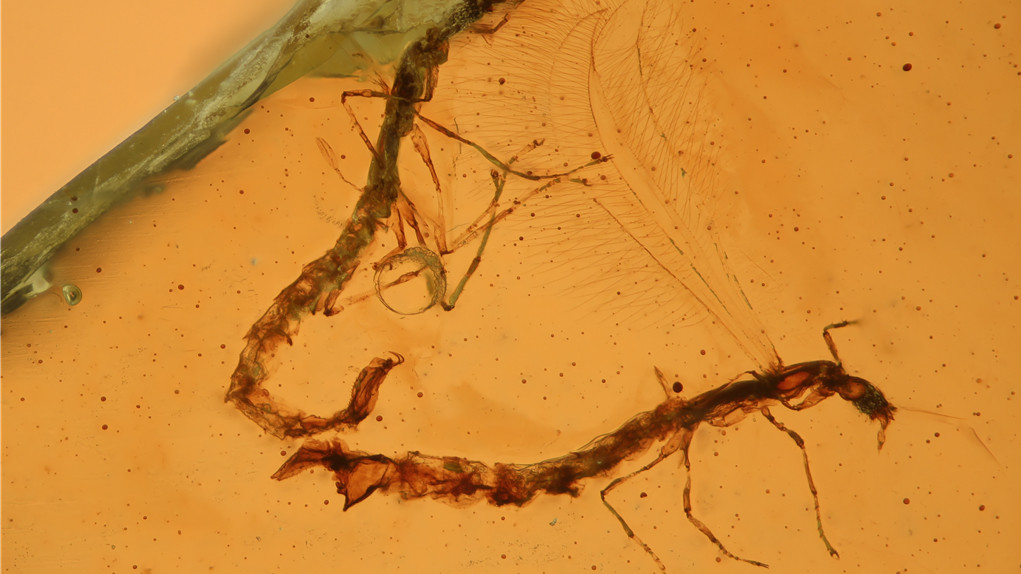

Image: Patrick Müller.The individuals of the new species Nymphomyia allissae are about 1 to 2 mm in size and have elongated, weakly veined wings. Compared to extant species, the wings have broader ends and are saber-like curved. "All in all, however, they look amazingly similar to their living descendants," said Prof. Dr. Rüdiger Wagner. "This mosquito genus has changed little and is thus a true successful model of evolution - just how successful is shown by our evidence that they existed around 100 million years ago."

Wagner found the specimens encased in Burmese amber, which is estimated to be about that age. Back in the Cretaceous period, dinosaurs such as the giant Gigantosaurus dominated the Earth. The oldest known fossils of the genus Nymphomyia previously known are estimated to be 35 to 40 million years old. In 1995, a fossil species was found in 25-million-year-old Bitterfeld amber and thus in Germany.

Present-day species are rare and occur in northern and eastern Asia and in North America. While the larvae and pupae live in cold streams, the adults fly in swarms - probably this was already the case with Nymphomyia allissae, because Wagner and a friendly amber collector found eight individuals in a piece of amber about 3.6 centimeters long. And still another commonality suspects the researcher: Adult animals of the today's species do not take up any more food. Relatively quickly after mating and egg laying they die. That this was already the case with the ancestors, "is very likely due to the head shape and not detectable mouthparts," says Wagner.

For the studies, the scientist cut the stone into smaller pieces, each with one or two inclusions, and then examined the animals microscopically, describing and classifying them. The results have now appeared in the journal Zootaxa.

Prof. Dr. Rüdiger Wagner held a professorship of limnology at the University of Kassel until his retirement in 2016.

Original article: doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4763.2.11

Press contact:

University of Kassel

Communications, Press and Public Relations

Tel.: +49 561 804-1961

Email: presse[at]uni-kassel[dot]de

www.uni-kassel.de

& nbsp;